Getting Started:

If you’re reading this, you’re probably already interested in photography and probably have a camera - or perhaps this has interested you in photography and you’re considering getting a camera - or this has inspired you to get more serious about photography and you’re now in the market for a new camera. Hopefully this hasn’t caused you to start piano lessons again! In any case, when shopping for a new camera, there are a few features that I look for, as well as a few questions I have to ask myself: (BTW - the following is primarily for digital cameras - if you’re interested in analog (film) systems, you’re probably already a seasoned photographer with your own preferences.)

Camera - Do I want an SLR or something more compact?

An SLR (Single Lens Reflex) or DSLR (Digital Single Lens Reflex) camera is one that accepts interchangeable lenses and accessories, providing more flexibility and options than a built-in lens camera. The drawback is that SLR systems are more bulky, and before you know it, you’ve got a bag full of lenses and accessories that you’re lugging around. The benefit...is that you’ve got a bag full of lenses and accessories that you’re lugging around, and you’re ready to shoot anything from extreme macro images to ultra-wide angle scenics - maybe you even want to attach your camera to a telescope or microscope - the flexibility is simply unmatched. If you’re leaning in the “SLR” direction, you’re buying much more than a “camera” - you’re buying your way into a system - so you may want to look into what that manufacturer’s system offers in the way of lenses and accessories for your camera. An SLR does you no good if the manufacturer only offers two lenses. Buy into the system that offers the accessories that you want or will possibly want in the future. As your system grows, you will find that the initial investment of the camera body is next to nothing compared to the accessories that you may acquire. The major manufacturers will always play “one-up” against each other - the “best” camera body from system A will be trumped by the best body from system B, and so on - so buy into the system.

If you’re not interested in all the accessories that an SLR provides, then you need to look at your purchase decision from a different angle. Most compact cameras offer some sort of “zoom” lens, that is, a lens that allows you to take wide angle shots as well as “zoom in” for a closer composition. Manufacturers will typically split this “zoom” range into two categories: optical and digital. The “digital” zoom range will always be considerably higher than the “optical” zoom range. Ignore the “digital” zoom range! Digital zoom is nothing more than taking a standard image, enlarging it, filling the gaps with digital “filler” and cropping it to fit the image area, which means that your image is a combination of the the scene you photographed and a bunch of artificial information thrown into the image by the camera. Instead, pay attention to the “optical” zoom range. The “optical” zoom of a camera is the true zoom ability of the lens, achieved by altering the arrangement of the lens elements within the lens. This is a true magnification of the lens optically without adding any digital noise.

Camera - Is it comfortable?

Before you buy a camera, get one in your hands, hold it up to your eye. Where do your fingers fall? Are they close to the controls that you’ll need to be accessing? Does your finger want to naturally fall right where the flash is, blocking it? (if so, your flash isn’t going to work very well). Is it too bulky, or, more likely, is it simply too small to operate comfortably? Is it too heavy - or too light? Personally, I prefer a camera that has some weight to it - not only does it just feel more sturdy, the extra weight makes it a touch easier to steady the camera when not using a tripod. Camera manufacturers keep making their cameras smaller and smaller, but they want the interface to be easy to navigate, so they’ve designed many of the cameras with “multi-function” buttons - meaning that the one button on the camera that’s actually large enough to press (without a ballpoint pen or surgeon’s scalpel) performs many functions, depending on the mode for which that button is set (changing that mode usually requires holding some other button while you press that button...so you can finally get to the setting you want to change - all with that one, easy to use button). Is that clear? I didn’t think so, which brings me to the next requirement:

Camera - Is it understandable?

SLR or compact, today’s cameras offer a plethora of features and options, but how easy is it to access those features? All of the features and settings in the world do you no good if they’re too difficult to get to or understand. Granted, there will be features, options and settings on virtually any camera that you may have to acquaint yourself with, but, once you learn them, are you going to constantly have to refer to the manual to re-learn how to use them? In an attempt to make photography “easier”, manufacturers have complicated the matter, incorporating so many features that are simply eye-candy and/or redundant that the process of understandable photography has become more of a secret ring than an expression of one’s creativity.

“My camera offers 37 different modes to choose from!”.

“Do you know what these modes mean?”

“No, but I have them at my disposal - just in case I ever figure them out!”

They will offer a mode that generates an exposure with the fastest possible shutter speed coupled with the largest possible aperture - and right next to that mode, they offer a mode that generates an exposure by coupling the largest possible aperture with the fastest possible shutter speed - but they’ll call the two modes different things, such as a “sports” mode and a “low light” mode. Heads I win, tails you lose! Of course, nobody’s going to fully understand every feature that a modern camera has to offer right out of the box, but you shouldn’t have to carry a manual around with you every time you want to take a picture.

Camera - Does the camera allow full manual override?

There are times when I honestly think I know better than the automatic modes of the camera how I want a photograph exposed - and I want tho option to set everything myself. My idea of metering may be different than the internal programming of the camera, or I may want to expose for something other than what the camera thinks it want correctly exposed. In any event, I want the option to have complete manual control of the camera.

Camera - Will it shoot when I want it to shoot?

Really - I want a camera that will take the picture when I press the button - and not all of them do. “Shutter Lag” is something to consider, especially if you’re shopping for a compact camera. “Shutter Lag” refers to the time delay between when you press the shutter release and when the camera actually takes the picture. Some cameras have a slight delay between the “pressing” and the “taking”, and, to me, that’s simply not acceptable. I want my photo taken “when I press the shutter release” - not “some time close to when I press the shutter release - there may be a slight delay...”.

Camera - Is there a remote release feature?

The question may sound a bit weird, but I want the ability to trip the shutter without having to actually physically press the release button, be it via a cable release or a remote. If I’ve spent the time setting up a tripod and perfecting a composition, I want to be able to trip the shutter without handling the camera, eliminating the risk of camera motion due to directly handling the camera. I want some method of triggering the shutter remotely, either electronically or mechanically by means of a cable release.

Camera - How many megapixels?

A “megapixel” is 1 million pixels. A pixel (PIX - Picture, EL - Element) is, generally, the smallest addressable unit on a display screen or digital image. OK, let’s leave the technical mumbo-jumbo behind - for all practical purposes, the higher the megapixel rating of a camera, the more detail the camera can record, meaning the larger the image can be displayed or printed without degrading. For example, a 6 megapixel camera will produce an image that will enlarge to roughly 8x10 at 300DPI (full print resolution).

Camera - Full Frame or Cropped Frame?

Focal lengths of lenses were determined back in the days of film cameras - and, in the case of a 35mm film camera, the image size on film was roughly 1.5” x 1” (35mm film is 35mm wide) - but many (typically lower end) DSLRs utilize a sensor that’s smaller than the “standard 35mm image area”. What this means is that your 28mm wide-angle lens converts to roughly 44mm (depending on manufacturer, the focal length is multiplied by a factor of 1.5 to 2). Higher end DSLRs have a full frame sensor.

If a DSLR, what about lenses?

The Lens - Definition

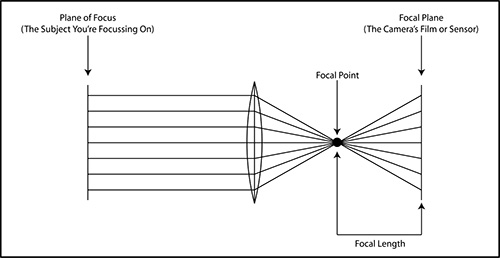

The lens is the eye of the camera, and it operates just like a human eye. All but the most simple lenses have multiple lens “elements” which are the individual pieces of glass (or optical plastic) shaped to organize light rays so that they can be focussed to produce an image. Just like the human eye’s iris, camera lenses have an adjustable opening called an aperture which controls the amount of light flowing through the lens by dilating or constricting. The diagram below illustrates how a simple lens works.

The Lens - Focal Length

Lenses come in a variety of “focal lengths”, from “wide angle” lenses to “ultra-telephoto” lenses - but what exactly does that mean? The focal length of a lens is defined (and represented) by the distance between the focal point of the lens (the point of convergence) to the focal plane (the image sensor of film). This distance is measured when the lens is focussed at infinity, typically presented in millimeters, for example: a “50mm lens” or a “300mm lens”. The 300mm lens is a “longer” lens than the 50mm lens. Telephoto lenses (longer lenses) have a more narrow angle of view than wide-angle lenses (hence the name). A more narrow angle of view means that the lens acts like a telescope - the longer the lens, the more narrow the angle of view, the stronger the telescopic ability of the lens. Many people refer to longer lenses as “zoom” lenses, in that these lenses allow you to “zoom in” on a subject, but the term “zoom” refers to a lens that can internally change its focal length. This does not always mean a telephoto lens - In fact, wide angle “zoom lenses” are common.

The Lens - Lens Speed

The “speed” of a lens refers to the light gathering ability of the lens and is determined by the maximum aperture available for that lens. For example, a common speed for a 300mm lens us f:4, meaning that the maximum aperture available on that lens is f:4, but there are faster (and consequently much more expansive) 300mm lenses available with speeds such as f:2.8. The faster a lens is, the less light needed to shoot with the same shutter speeds. Fast lenses are typically much more expensive, heavy, and physically larger then their slower equivalents, but not necessarily any sharper.

The Lens - Perspective

Many people believe that lenses affect perspective, but that’s not quite true. “Perspective” refers to the relative distances between objects and your location relative to those objects. As you move, the perspective of any scene changes. Longer lenses appear to compress space, and wider lenses appear to expand space, but this appearance is simply because the photographer is changing his position relative to the subject. For example, to fill the frame with a subject that is 5 feet tall, I can use a 300mm lens from about 70 feet away, or I can use a 28mm lens from about 6 feet away. At 70 feet, things that are 4 or 5 feet from my subject appear to be pretty close to my subject - after all, what’s 4 or 5 feet when you’re 70 feet away? But, when I’m shooting from 6 feet, objects 4 of 5 feet from my subject look like they’re really far from the subject. The fact that wider lenses appear to “stretch” the perspective is due to the fact the the photographer needs to get much closer to the subject to achieve the same composition.

The Lens - Focusing

Many lenses focus by turning the front of the lens like a screw, moving the front series of elements. Some lenses, however, utilize an internal focussing technique - rearranging the internal elements to achieve focus. There are a couple of advantages to this internal focussing method. 1: The front of the lens doesn’t physically turn. This is usually no big deal - until you are using a polarizer filter and that turning motion alters the filter’s setting. 2: The lens doesn’t grow longer, something that can make close-up work a bit more complicated.

So you now have your camera, and, hopefully, you have some sort of lens on the camera. Now what?